GEORGE COSTAKIS – THE SAVIOR OF THE RUSSIAN AVANT-GARDE

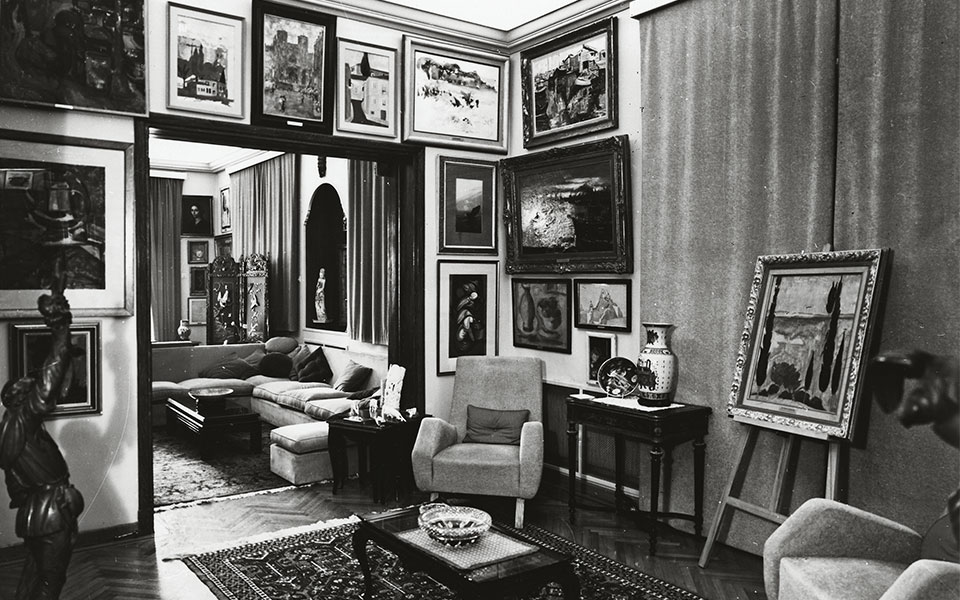

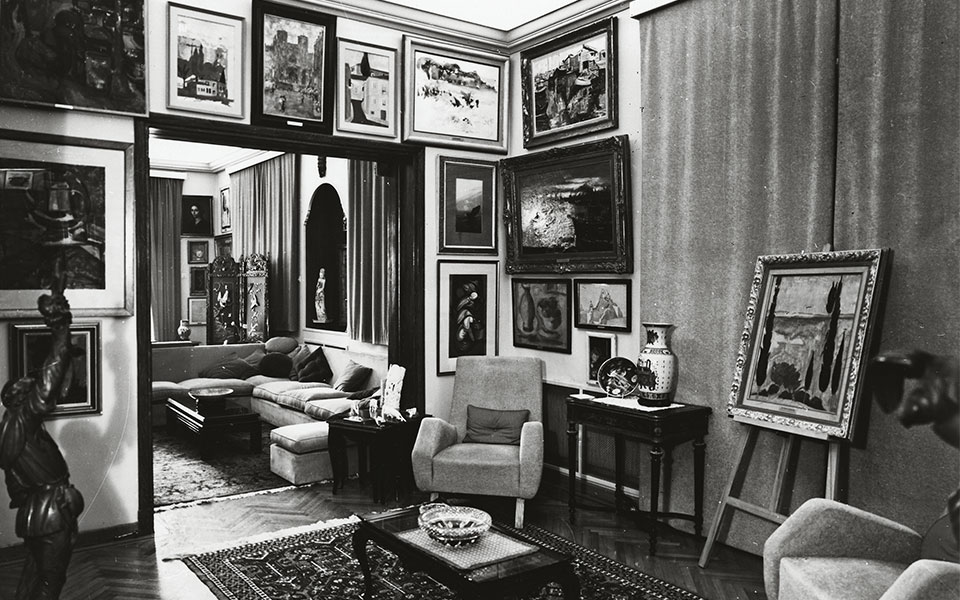

“In 1960s Moscow, there were two places that official state visitors wanted to see: the Kremlin and George Costakis’ apartment,” says Dr Maria Tsantsanoglou, director of the State Museum of Contemporary Art (SMCA), referring to the home of this dynamic, purposeful collector, who amassed a vast and comprehensive art collection.

The apartment everyone wanted to visit comprised three modest rooms whose walls were covered with works of the Russian avant-garde; it was the only place where such a collection could be seen. A diverse crowd of intellectuals, artists, students and foreign visitors gathered nearly daily. Chagall came; Stravinsky came; a provincial school of art visited one morning and then, later that same day, David Rockefeller. In this contemporary salon, they would drink, engage with one another about art, and even break into song.

George Costakis was born in Moscow, where his father, a merchant from Zakynthos, had settled. George worked as a driver for the Greek Embassy and later took a job at the Canadian Embassy. In the course of his work, he would sometimes accompany foreign visitors to art galleries and antique stores. He had a good eye, so he, too, started collecting – old Dutch Masters, porcelain, silver – although without particular passion. As he said later, “I kept thinking that, if I continued in the same vein, I wouldn’t contribute anything to art … Everything I collected was already shown in the Louvre or the Hermitage … by sticking to this, I could get rich, but nothing more.”

In 1946, he chanced upon his first avant-garde work. His daughter Aliki said it was likely a cubo-futurist painting by Olga Rozanova. He took it home and hung it beside the Dutch Masters and then contemplated it: “I had a feeling I’d been living in a room with curtains drawn, and now they were open and sunlight was streaming in through the windows. At that moment, I decided to part with everything I’d collected, and started buying nothing but avant-garde.”

Costakis turned to art historian Nikolai Khardzhiev for advice. Khardzhiev told him that the names of only a few artists, such as Kandinsky, Tatlin and Malevich, would survive. He also said that the movement was finished, not worth pursuing. If anything, the conversation only strengthened Costakis’ resolve; he likened his pursuit to archaeology, determined to bring the avant-garde to light “as Schliemann had unearthed Troy.”

Info

State Museum of Contemporary Art

21 Kolokotroni, Moni Lazariston

Tel. (+30) 2310.589.143

Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, Thu 10:00-22:00

Admission: €4

© State Museum of Contemporary Art - Costakis Collection, photo: Henri Cartier-Bresson

© State Museum of Contemporary Art - Costakis Collection, photo: Igor Palmin

Tsantsanoglou puts it a little differently: “George Costakis formed this great collection in the period between 1946 and 1977, fully aware he was fulfilling a mission: the mission of saving Russian avant-garde art from disappearance.”

This venture was unprofitable; as Costakis later recalled: “Among the circles of collectors in Moscow I had the not-so-flattering nickname ‘the Mad Greek’ who collects useless garbage.” It was also risky; by the 1930s, socialist realism had become the sole acceptable form of artistic expression in Soviet Russia. As the Stalinist state began to persecute the avant-garde, works were hidden away, sometimes for decades, in closets and under beds. This lent urgency to Costakis’ mission. Piece by piece, he rescued works. He sought out sketches, correspondence, manifestoes, educational materials, posters and magazines, creating an encyclopedia of the avant-garde.

“A real collector must feel like a millionaire, even when he is penniless,” was one of his precepts. “He’d buy a car, then sell it a few days later to buy a painting,” Tsantsanoglou relates. “When he gave his wife Zina a fur for her birthday, he asked for it back three days later. She loved the fur but wanted the painting more.” His daughter Aliki went to Leningrad to buy a painting for him; as a foreign citizen, his travel was restricted. “We all loved art,” she said. “We were in it together.”

By the 1970s, given his social circle, his free views and his outspoken defense of art were labeled “degenerate” by the authorities, his situation had become increasingly precarious. He began plans to emigrate. As a condition of receiving his exit visa, he gave 80 percent of his collection to the State Tretyakov Gallery. Ultimately, he wanted the works to be seen: “I’m against people having collections for themselves.”

The works that came with him to Greece are now in the SMCA. After a stay at Istanbul’s Sakip Sabanci Museum, the exhibition “Thessaloniki. Costakis Collection. Restart,” which celebrates his vision, will return to the SMCA in April 2019.

© Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art Collection, Courtesy of Alexander Iolas

alexander iolas – THE CHARISMATIC one

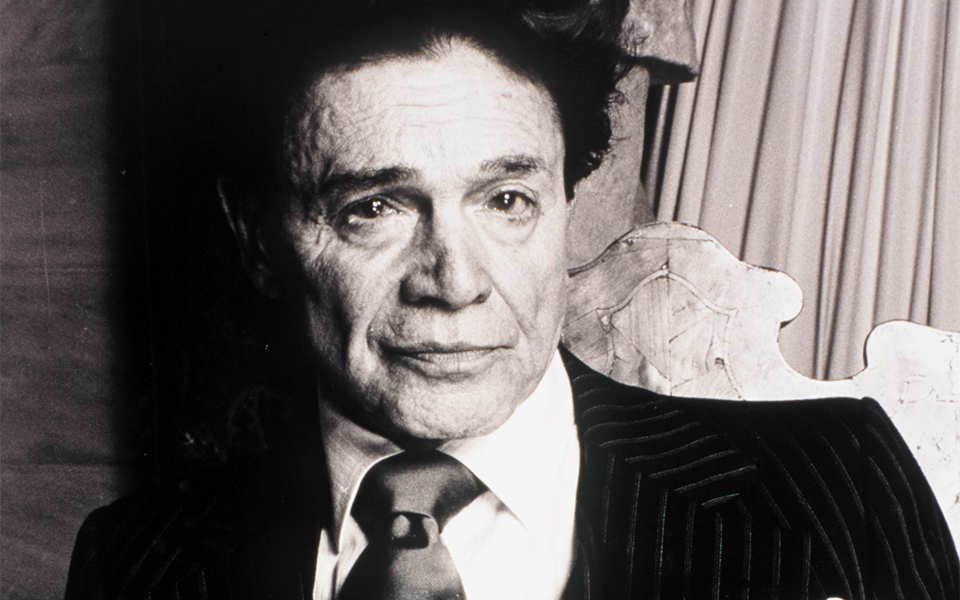

Among the many captivating personalities of the 20th-century international art world, Alexander Iolas was unique. This charming cosmopolitan man had a clear vision, which he followed by discovering and representing artists who would shape the world of modern art. Today in Thessaloniki, this vision is being explored at the museum he helped found.

Iolas’ story is intriguing from the very start: born in 1908 into a wealthy Greek family of cotton merchants in Alexandria, he left the Egyptian port-city for Athens in 1927, with a letter of reference from the poet Constantine Cavafy to pursue the discipline of dance. From then on, he’d find himself continually engaging with people of culture and intellect. He moved to Berlin in 1931, where he became acquainted with composer Kurt Weill and author Thomas Mann. In 1933, after the Nazis came to power, he left for Paris, where he acquired his first artwork – a piece by Giorgio de Chirico, who became a close friend, and formed acquaintances with René Magritte, Max Ernst, Man Ray, Raoul Dufy and others.

He left for New York around 1935, becoming a principal ballet dancer there. He eventually stopped dancing due to an injury, and changed course; in 1945, he became director of the newly established Hugo Gallery. The gallery gained instant, enthusiastic recognition, as expressed in a review of the opening show in the New York Times: “The Hugo Gallery, dedicated to the avant-garde, has entered New York’s art-world roster … You have to just reject the rational, resist it like mad at every turn, and the magic will begin to work.” Some time later, he met Andy Warhol, stopping him on the street in front of the gallery to see what was in his portfolio – his sketches of shoe designs for the factory where he worked. Iolas arranged Warhol’s first solo exhibition – a series of drawings based on the works of Truman Capote. Iolas and Warhol would remain friends for the rest of their lives.

Around 1955, the gallery in New York became his, and was renamed Iolas Gallery. A series of galleries throughout Europe followed: Paris, Rome, Milan, Geneva, Madrid, Athens (Iolas-Zoumboulakis). Over the next two decades, he would work with many seminal artists, including Ernst, Magritte, Kounelis, Tanguy, Calder, Miro, Dali, Picasso, Takis, de Saint Phalle, Klein and, of course, Warhol, artists who defined the major movements of the 20th century: surrealism, pop, arte povera, nouveau réalisme and minimalism. His galleries became destinations: “Being in New York and not visiting Iolas’ gallery,” Margot Fonteyn told Jackie Kennedy in 1968, “is like being in Greece and not visiting the Parthenon, or being in Rome and not visiting the Vatican.”

Info

“Alexander Iolas: The Legacy”

until January 20, 2019

Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art

154 Egnatia (inside HELEXPO grounds)

Tel (+30) 2310.240.002

Thu 10:00-22:00, Fri 10:00-19:00, Sat 10:00-18:00, Sun 11:00-15:00, Mon-Wed closed

Admission: €4

Accounts of Iolas often refer to his notably arresting persona, his rare style and charisma: he was remembered in the New York Times for being able to reassure collectors “with his hierophantic manner, his often sensational mode of dress, and his mischievous and sometimes irresistible charm.” But he was also a person of substance who had meaningful relationships with the often prominent artists he represented, collaborations that contributed to their creativity. Some of his friendships were marked by significant acts, such as closing all his galleries – except the one in New York – after the death of Max Ernst, in fulfillment of a promise he had made to him.

In Greece, he was pivotal in changing the country’s cultural landscape. After the 1978 earthquake in Thessaloniki, his close friend Maro Lagia proposed a dynamic response to the damage the city’s monuments had suffered: a center for contemporary art. Iolas had considered making a major donation to the Greek state but that ultimately fell through, making this entirely private initiative his only actual bequest to Greece. The almost 50 works that Iolas gave formed the core of the collection of the Macedonian Center of Contemporary Art (later the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art).

The MMCA’s director, Thouli Misirloglou, admires the collection’s global sensibility: “What is interesting about Iolas’ donation is the mingling of international and Greek artists. Tinguely, de Saint Phalle or Martial Raysse are not very far, artistically, from the Greeks Akrithakis, Tsoclis or Pavlos. Of course, Iolas didn’t really care about nationalities. ‘Artists don’t have a passport,’ he’d say. Takis, for example, was seminal for Iolas (and the MMCA) not as a Greek artist, but as an artist whose nationality was irrelevant.”

Sharing this cosmopolitan perspective with the Greek public was pivotal. When the Macedonian Center of Contemporary Art opened, it was the only institution for contemporary art in the country. The MMCA’s exhibition “Alexander Iolas: The Legacy” celebrates an extraordinary individual, his collection and the sense of excitement and discovery he brought to art.

© T.I.T 1999.176 Teloglion Foundation of Arts A.U.TH Collection

ALIKI & NESTOR TELLOGLOU – The Philanthropists

On the top floor of a building facing Aristotelous Square is the apartment of Nestor and Aliki Telloglou. Small groups visit periodically, by appointment. It’s a wonderful home, elegant in its modest proportions. The rooms are eclectically furnished, with rustic pieces mixed with mid-century modernism, and filled with wonderful objects: Chinese sculpture and Asian pottery (18th-19th centuries), Persian miniatures, and photos, souvenirs and mementoes acquired on the couple’s travels. It was and still is a place for lively engagement with art and culture. The paintings, hung floor to ceiling, have a tremendous presence.

When the Telloglous married in 1955, they started buying art at once. The resulting collection includes significant 19th and 20th-century Greek artists such as Gyzis, Parthenis, Maleas, Lytras, Kontoglou, Gounaropoulos, Hadjikyriakos-Ghika, Georgiadis, Engonopoulos, and Spyropoulos. While it’s a fine introduction to different currents in Greek art – from academicism to the “Generation of the ’30s,” modernism, surrealism and abstraction – the growth of the collection was organic and personal. The common factor among the works is simply that they were all adored. As Aliki put it, object and meaning were inseparable: “Works of art were among the first friends who came, one by one, to our home … We moved each of these works when we acquired it from room to room, wherever we sat, to be able to get to know it, to listen to its voice and feel it as our own.”

Travel deepened their appreciation of the universal necessity of art, causing them to reflect on the role of art in Greek life and to note that not only was art education largely absent from Greek schools, but that many people, especially in rural areas, lacked both the awareness and the means to seek out art in museums. Realizing this inspired them to, in Aliki’s words, “open a school that would speak about the way in which man and art come to an understanding.”

Info

Teloglion Fine Arts Foundation

159A Aghiou Dimitriou

Tel. (+30) 2310.247.111

Tue-Fri 09:00-14:00, Wed 09:00-14:00 and 17:00-21:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-18:00

Admission: €5

For Telloglou House tours, Tel. (+30) 2310.991.610, Admission: €5.

Happily, they had the resources and skills to achieve this. Nestor came from a philanthropic background. His family had been merchants and bankers in Smyrna, and benefactors to their region before coming to Thessaloniki. Aliki possessed a rare sensitivity to art, and the determination to realize such a project.

In 1971, they arranged with the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki to donate their collection and to dedicate the funds required so that the university could host a future institution to be known as the Teloglion Fine Arts Foundation on its grounds. Establishing the foundation would prove to be a tremendous undertaking, made even more difficult by the death of Nestor in 1972, although his widow Aliki, who ended up realizing the dream for both of them, insisted that his passing had in no way diminished “his contribution to the Teloglion.”

The foundation opened in 1999, after nearly three decades of effort. Community engagement is at its heart: theater, dance, music, and literary events, as well as colloquiums and symposiums engage the community in art and culture. A fantastic museum space hosts exhibitions of local and internationally renowned artists, including Miro, Delacroix and Toulouse-Lautrec. Parallel to this, selected works from the Teloglion’s permanent collection, which has a particularly strong focus on modern Greek art, are displayed at the Teloglion on a rotating basis, as well as at the Telloglou House.