The art of tattooing has undergone something of a “renaissance” in recent decades. No longer associated with counterculture or rebellion, tattooing has become a mainstream form of self-expression for people of all backgrounds and professions and transcending all social boundaries. In fact, a recent survey by the US-based Pew Research Center reported that nearly one in three American adults have a tattoo, including 22% who have more than one!

If you are a member of this rapidly expanding demographic, you belong to an ancient tradition that stretches back at least 5,000 years to the Neolithic, or “New Stone Age,” as evidenced by the discovery of dozens of “inked” mummified human remains from various regions around the world. Some scholars argue that tattooing has an even greater antiquity, being practiced by our hunter-gatherer ancestors as far back as the Upper Palaeolithic (“Old Stone Age”).

© Public domain

© Public domain

Whatever their temporal origins, these early tattoos were created using simple tools like sharpened bones, sticks, or razor-sharp flakes of obsidian (a volcanic glass-like rock) to introduce pigment into the skin, including charcoal soot, plant resin and ochre, mixed with animal fat. Anthropologists believe that these earliest markings held significant spiritual and cultural meanings, serving as conspicuous displays of identity or as ceremonial rites of passage (reaching adulthood, for example).

Over the millennia, tattooing traditions developed in many indigenous cultures around the world, most famously among the various Austronesian peoples of Southeast Asia and the Indo-Pacific (e.g., the Māori, Samoans, and Hawaiians), the Native Americans, and the ancient Japanese. The word “tattoo,” which is believed to have originated from the Tahitian word “tatau,” meaning to mark, was introduced into the English language in the late 18th century following the exploratory voyages of British navigator and cartographer, Captain James Cook, in the South Pacific.

But what do we know about the origins and early development of tattooing here in Europe? And specifically, among the ancient Greeks? What archaeological evidence is there for tattooing in ancient Greece? And what do we know about their attitudes towards tattoos?

© Zigres - Shutterstock

© Public domain

Geometric Patterns and Parallel Lines

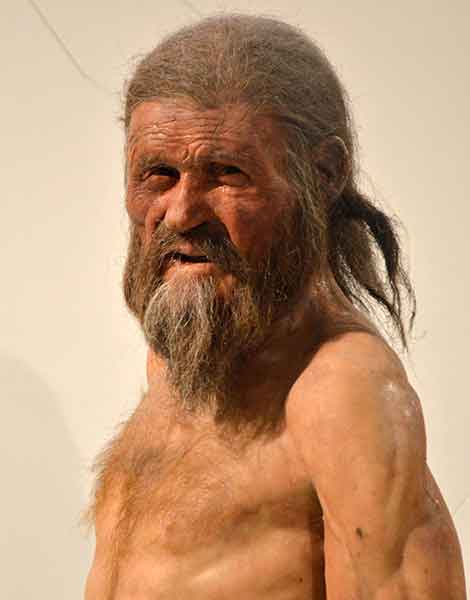

The earliest direct evidence for tattooing in Europe comes from the Chalcolithic (“Copper Age”), which lasted from c. 5000 to 2000 BC. The most significant findings are associated with the mummified remains of Ötzi “the Iceman,” discovered in 1991 by two German hikers, embedded in the glacial ice of the Ötz Valley in the Alps, on the border of Austria and Italy. Scientists discovered that Ötzi’s well-preserved skin was heavily tattooed, bearing a total of 61 individual markings, making them the world’s earliest known tattoos, dated between 3350 and 3105 BC.

Ötzi’s tattoos consist of simple, geometric patterns made up of dots, lines, and one cruciform mark, and are distributed across various parts of his body, including his lower back, wrists, ankles, and legs. Forensic analysis of his remains revealed they were created by making small incisions in the skin and then rubbing charcoal or other dark pigments into the wounds. While the exact purpose of Ötzi’s tattoos remains a subject of scholarly debate, some theories suggest they had therapeutic, medicinal, or ritualistic significance. The placement of the markings near areas of his body that show evidence of physical stress or injury has led some researchers to propose that they may have had a therapeutic purpose, similar to acupuncture or acupressure.

In the later Iron Age, from c. 500 BC onwards, Greek and Roman writers, including the historian Herodotus (c. 484-425 BC) and the Roman general and statesman Julius Caesar (100-44 BC), described the various tribal peoples of the British Isles and northern mainland Europe as having tattoos, including the warlike Picts (from “Picti,” meaning “painted people”), the indigenous inhabitants of northern Scotland. However, unlike Ötzi, who was discovered with well-preserved tattoos, no preserved Pictish bodies or mummies have been found to provide direct evidence of tattooing. Instead, Pictish art, known for its intricate and enigmatic symbols and geometric designs, may have simply been painted body markings rather than permanent tattoos.

© Public domain

© Public domain

Painted Statues

In the Mediterranean world, tattooing was practiced among certain religious and cultural groups, most notably the ancient Egyptians, with evidence of figurative tattoos dating back to around 3000 BC (nearly contemporaneous with Ötzi the Iceman). In later periods, tattooing appears to have been an exclusively female custom within Egyptian society. Women would adorn themselves with intricate tattoos, often on their upper thighs, breasts, and abdomens, as permanent amulets to encourage fertility or protection during pregnancy. Several high-status female mummies dated to around 2000 BC bear the tattoo of the household deity Bes, the patron of fertility and protector of women, inked on their upper thighs. Egyptologists believe these tattoos may have served as protective amulets to ease the pain of childbirth.

In the 3rd millennium BC Aegean, scholars have suggested that the practice of tattooing was widespread among the Early Cycladic culture, as evidenced by the traces of bright red and blue pigment found on their enigmatic marble figurines. In addition, the numerous obsidian blades found in Cycladic graves have been variously interpreted as implements for shaving, tattooing, and body scarification, suggesting a link between the painted figurines and the practice of body modification. Artistic motifs on the statues, sometimes described as “idols,” often emphasize anatomical features related to biological sex, such as the breasts and genitalia. More abstract motifs, usually confined to the head, include dots and zigzags. Could these represent tattoos?

While there is no direct archaeological evidence for tattooing in the prehistoric Cyclades by way of mummified bodies, unlike in the hot, desert conditions of Egypt, it remains an intriguing possibility that early islander communities in the Aegean regarded their bodies as blank canvasses that could be adorned with various symbols or messages concerning identity and status.

© Public domain

Greeks and Barbarians

By the time we reach the 5th century BC, and the cultural flourishing of Classical Greece, several written sources and inscriptions provide us with key insights into the ancient Greek perception of tattoos, and how they used tattoos themselves. Herodotus, for example, mentioned the practice of tattooing among the neighboring Thracians to the north (modern-day Bulgaria, Romania, and northwest Turkey), whose culture was described as “tribal and warlike.” Herodotus noted that the custom of tattooing was common among both men and women, and that they used ornate tattoos as a form of personal identification and to mark their achievements: “To be tattooed is a sign of noble birth, while no tattoos signifies lower status. One who does not work the earth is most honoured, while the tiller of the soil goes unhonoured; he who lives by war and raiding is held in highest honour” (Herodotus, 5.6.2).

Other peoples of the Western Eurasian Steppe (modern-day Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan, and Central Asia), including the nomadic Scythians, were known by the Greeks to be tattooed. The Scythians were renowned for their horsemanship and skills in mounted warfare, frequently raiding neighboring territories. They were also known for their highly stylized art, particularly their gold and metalwork, often featuring fantastical creatures and intricate animal motifs. Evidence for their tattoos has been found one the skin of well-preserved Scythian mummies, most notably the “Man of Pazyryk,” buried sometime between the 5th and 4th centuries BC. This warrior chieftain, discovered at Pazyryk, Russia, was heavily tattooed with elaborate zoomorphic symbols, including fish, monsters, and a series of dots that run along his spinal column. Tattooing amongst these tribal cultures was clearly seen as a mark of pride.

Of course, this view did not translate over to Herodotus’ own society, who saw them as a mark of degradation and servility. The Greek word for tattoo was “dermatostiksia,” deriving from the affix “derma” (skin) and the word “stigma” (mark), suggesting a strong negative connotation. We know that the Greeks placed a high value on physical beauty (“kalos”) and the natural state of the body. Tattooing, or any form of branding or body modification, would have been seen as a deviation from this ideal. As such, the practice was perceived as a defacement of the body and an alteration of its natural form. Furthermore, their association with “otherness,” specifically with so-called “barbarian” cultures, contributed to the negative perception, as the Greeks considered themselves culturally superior to other groups.

© Public domain

© Public domain

Floral Designs and a Ptolemaic King

But not all Greeks viewed tattoos in such negative light. In the early 4th century BC, the Athenian-born writer, historian, and military commander Xenophon (c. 430-355/354 BC) wrote a first-hand account of the adventures of a 10,000-strong mercenary army, hired to help Cyrus the Younger seize the throne of Persia. The “Anabasis,” meaning “ascent,” was composed sometime around 370 BC, and describes encounters with tattooed people in the southern coastal regions of the Black Sea. The “Mossynoikoi” were said to be heavily tattooed, with various floral shapes and designs inked across their bodies (Xenophon, Anabasis, 5.4.32). In his account, Xenophon uses the word “poikilous,” which could mean “multi-colored” or “spotted,” implying embroidery or weaving. In other words, he is hinting at the fact that the tattoos were decorative.

Intriguingly, Ptolemy IV Philopater (244-204 BC), the fourth pharaoh of the Macedonian-Greek dynasty that ruled Egypt from 305-30 BC, was said to have been tattooed with ivy leaves, symbolizing his devotion to Dionysus, god of wine and revelry, and the patron deity of the Ptolemaic royal household at the time. Known for his decadent lifestyle and ambivalence to the affairs of state, ancient sources cite his reign (221-204 BC) as the start of the steady decline of the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt. Nevertheless, it is interesting that a Greek-speaking ruler embraced the conspicuously “uncivilized” and “barbarian” practice of tattooing, at a time when the city of Alexandria rivalled Athens as the intellectual powerhouse of the Mediterranean world.

© Shutterstock

“Stigmata”

Ancient Greek sources also attest to the practice of tattooing or branding prisoners of war. According to Herodotus, the Thebans who surrendered at the famous last stand at Thermopylae in 480 BC, were presented to the Persian king, Xerxes, and tattooed “with the kings marks” (Hdt. 7.233.2). As such, a tattoo received as a war captive was a mark of cowardice and defeat.

Inspired by this practice of tattooing war captives, the Greeks subsequently adopted it during later conflicts, oftentimes against fellow Greeks. One such example is described by the writer and historian Plutarch (c. 46-119 AD), in his account of the Athenian statesman Pericles and his military expedition to suppress a revolt by the oligarchical government of Samos in 440-439 BC. During the conflict, both sides tattooed their captives on the foreheads, the Samians with owls (the mark of Athens), the Athenians with a “samaina,” a distinctive-looking warship with a “boar’s head design for prow and ram” (Plutarch, Pericles 26.3). A similar indignation befell Athenian captives a generation later, during the disastrous Sicilian Expedition of 415-412 BC. Prisoners were “branded in the forehead with the mark of a horse” (Plut., Nicias 29.1), the symbol of the Syracusans, marking them as property of the state.

© Public domain

© Public domain

Criminals and slaves

The most widespread use of tattooing in ancient Greek society was to penalize criminals and slaves. Several comedies by the Athenian playwright Aristophanes, composed in the late 5th century BC, describe tattooed slaves or disobedient slaves being threatened with the punishment of a tattoo. Indeed, the custom of tattooing a slave, which usually involved inking the letter “Δ,” the first letter of the word “doulos” (slave), on their forehead or another easily visible location, confirmed their status as being the physical property of their owner. A scholion (commentary) by the Athenian statesman and orator, Aeschines (389-314 BC), chillingly describes how runaway slaves were tattooed on the forehead with the inscription: “Stop me, I’m a runaway.”

By the same token, criminals in ancient Greece were tattooed on visible parts of their body with letters or symbols that indicated their crime, e.g., thieves or money swindlers. Penal tattooing was eventually outlawed as Christianity became the dominant religion in the Roman empire. Constantine the Great (272-337 AD) banned facial tattoos in 316 AD, declaring that “man has been created in the image of God and to so defile the face is to disgrace the Divine.” Later, the practice was completely abandoned, due to its links to paganism.