Dionysus, the ancient Greek god of wine, often seems a familiar, likable figure, perhaps because wine and its associated rituals are such a characteristic ingredient of our own modern-day existence. Like other deities, Dionysus appears in human form and is credited with divine powers; yet thanks to his love of drinking, dancing, music and uninhibited merry-making with free-spirited friends, he offers an even more evocative reflection of the human condition and represented a favorite figure in ancient Greek religion and art.

Dionysus was the son of Zeus, ruler of the Olympian gods, and Semele, a Theban princess and daughter of King Cadmus. After his mother was tricked and killed by Hera (Zeus’ vengeful wife), Dionysus was rescued from Semele’s womb by his father and implanted in his thigh. On his son’s birth, Zeus placed Dionysus in the care of nymphs who inhabited the mythical mountain Nysa – variously located by mythologists somewhere to the east, perhaps even in distant India. As he matured, Dionysus took up wandering from land to land, accompanied by an entourage that included his tutor, Silenus, satyrs, maenads and the lustful god Pan, a human-like figure with the horns and legs of a goat. Silenus was the leader of the satyrs: hybrid woodland creatures envisioned as men with horses’ ears, tails and sometimes legs. The maenads were “raving” women inspired by Dionysus, who also loved drinking, dancing and attaining a state of ecstasy. Dionysus took as his wife Ariadne, who had aided Theseus in escaping the labyrinth at Knossos before being left by the Athenian hero on a Naxian beach. After Ariadne’s death, Dionysus entered Hades and brought both her and Semele to Mt Olympus to live as immortals. In ancient art, Dionysus is often pictured carrying a thyrsus, a wooden staff entwined with ivy and capped with a pine cone and vine leaves.

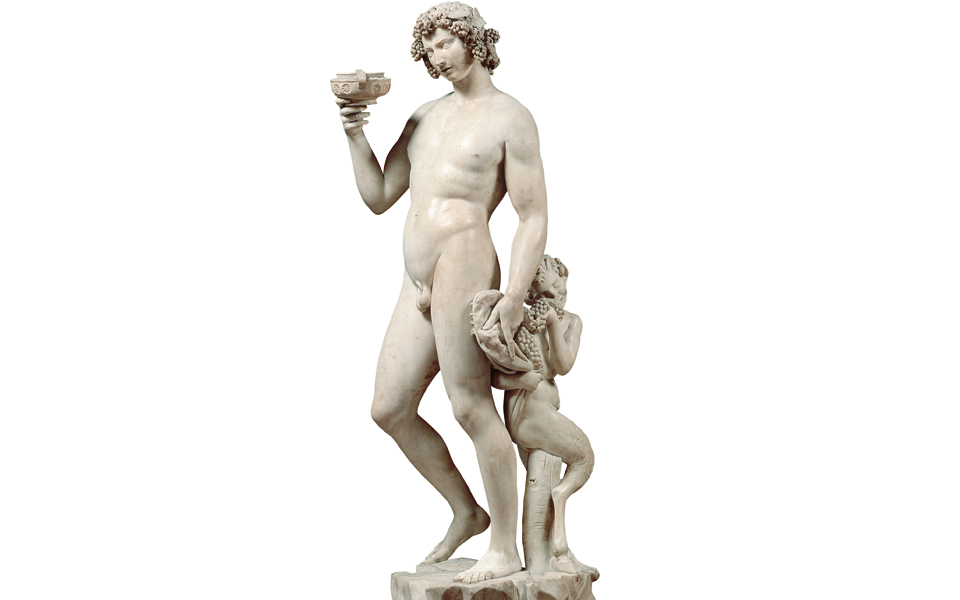

“In ancient art, Dionysus is often pictured carrying a thyrsus, a wooden staff entwined with ivy and capped with a pine cone and vine leaves.”

(Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence)

Dionysus fathered several children with Ariadne, including Oenopion (“wine-drinker”) and Staphylus (“grape-related”), who became an Argonaut, a general and the founder of Peparethos, a colony on Skopelos. He also had a son with Aphrodite, who became a favorite figure in Roman times – Priapus, the well-endowed, ithyphallic god of male procreative power.

Religious worship of Dionysus came to Greece from Asia Minor; perhaps, as Homer intimates, via Thrace. Similar prehistoric gods already existed, at least by the second millennium BC, whom Dionysus absorbed. He was considered a latecomer to the Greek pantheon and an exotic, somewhat foreign divinity. His cult entered Attica from the direction of Thebes, first being established at a temple just inside the Attica/Boeotia frontier, at a spot later overlooked by the border fort of Eleftheres. From there, his wooden cult statue (xoanon), according to the traveler Pausanias, was transferred to Athens. Another ancient tradition holds that the wandering Dionysus befriended Icarius, a farmer from the deme of Icaria just north of Mt Penteli, whom he taught to grow grapes. Afterwards, an autumn harvest festival emerged that included feasting, drinking and music – believed by some scholars to have spawned other such rural celebrations and ultimately the City Dionysia in Athens. Thespis, another legendary Icarian, is said to have first brought theatrical performances to Athens, where he was the earliest-known actor to win a prize (534 BC) at the City Dionysia.

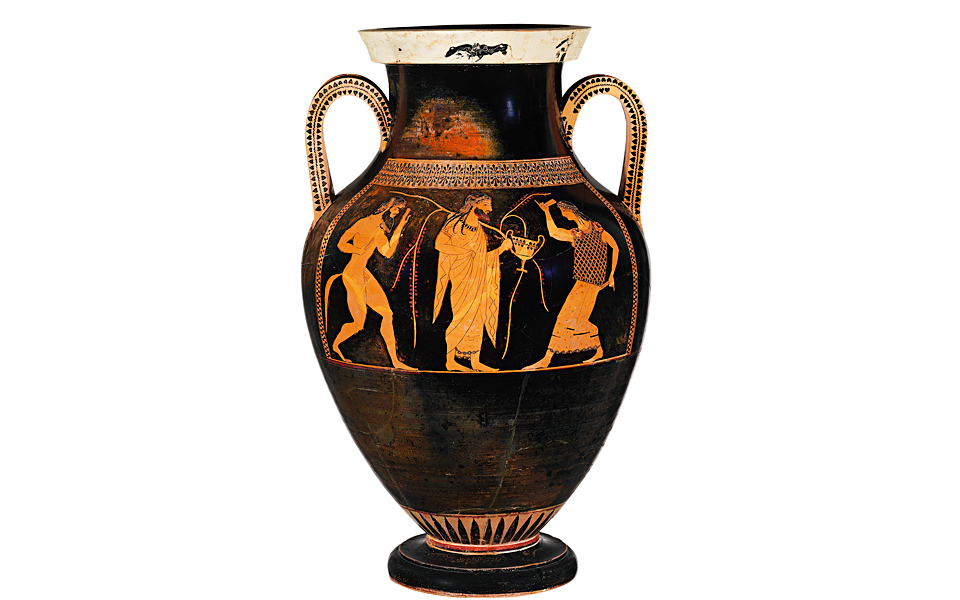

Dionysus was considered a latecomer to the Greek pantheon and an exotic, somewhat foreign divinity.

(Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

As the god of wine, Dionysus was a popular figure worshiped regularly in Athens, especially at nightly aristocratic drinking parties, symposia, which were all-male occasions for drunken camaraderie, music, hired female entertainment and ultimately orgiastic communal sex.

Athenians honored Dionysus in a series of annual festivals, celebrated at three key spots sacred to the god: the “Lenaeum” (location unknown); the sanctuary “In the Marshes” (location unknown); and at his temple on the south slope of the Acropolis, adjacent to the Theater of Dionysus. The main features of these events included processions, sacrifices, feasting, drinking, music, jesting, mockery, the singing of dithyrambs (wild, choral songs or chants) and the performance of tragedies, comedies and ribald satyr plays.

(Princeton University Art Museum)

The Rural Dionysia (December/January) were small celebrations held by communities at various sanctuaries outside Athens, to which urban residents would travel on festival days. The larger City Dionysia (March/April) focused mainly on the carrying of Dionysus’ wooden cult image from the Lenaeum to his Acropolis-slopes temple and on a three-day theatrical contest in which new plays were presented. The Lenaea (January/February) also featured a theatrical contest and a lavish public banquet with meat provided at state expense. The Anthesteria (February/March) celebrated the opening and tasting of the maturing wine from the most recent vintage. Also, the wife of the King Archon, a leading state official, was ceremonially wedded to Dionysus at the Lenaeum. Lesser festivals included the Oschophoria (October/November), when vine clippings bearing ripe grapes were carried by noble-born youths (ephebes) in a footrace from Limnae (southern Athens) to coastal Phaleron. The Haloa harvest festival (December) was celebrated almost exclusively by Athenian women, but primarily staged at the sanctuary of Demeter at Eleusis. It featured the dedication of first fruits (grapes, grain), accompanied by lusty activities and sex-related symbols and confections.

The Theoinia was a local form of Dionysian worship, celebrated with feasts and sacrifices at small shrines. It often involved select families whose ancestors were believed to be direct descendants of Dionysus’ original followers. The Bacchanalia was the Roman-era festival of Dionysus (Bacchus). Two of the most illuminating ancient texts concerning Dionysus are the seventh Homeric Hymn (7th/6th cent. BC) and the Bacchae of Euripides (405 BC). Aristophanes’ comedy The Acharnians (425 BC) offers a humorous glimpse of the Rural Dionysia. On the Homeric Hymn’s telling of Dionysus being captured by pirates and his transformation of them into dolphins, with the exception of their helmsman, Robin Osborne (2014) concludes: “Few recognize Dionysus as a god…and only those who do retain their humanity.”