The Antikythera wreck, renowned for its cargo of bronze and marble statues and the corroded remains of a sophisticated clockwork mechanism, is once again the focus of cutting-edge underwater archaeological research.

The findings of the latest survey and excavation of the Roman-era wreck, carried out between October 1-10 by members of the Swiss School of Archaeology and the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, include more fragments and intact ceramics from the ship’s cargo and the collection of high resolution photogrammetric data that will one day enable virtual access to the site.

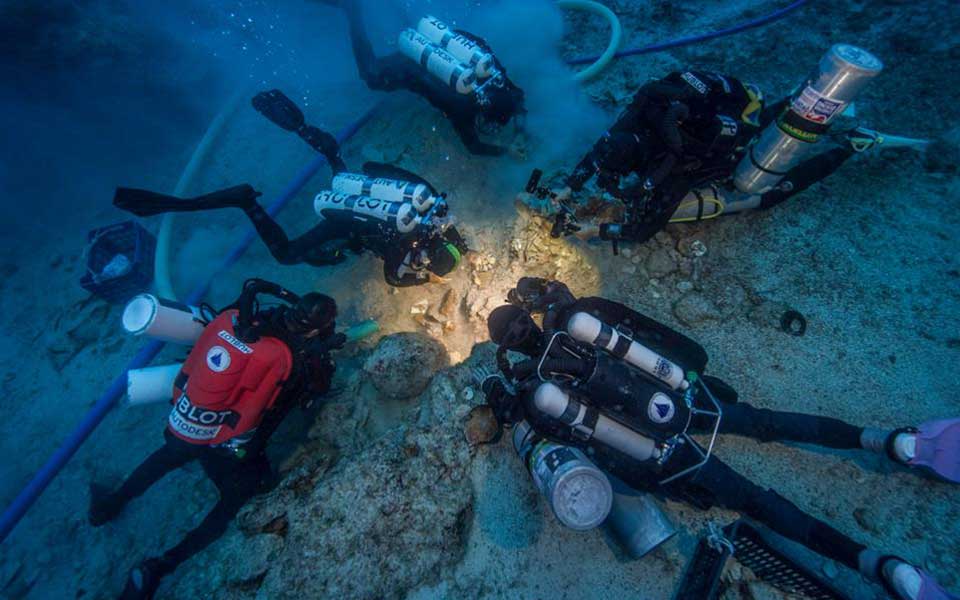

Over the course of the season, the team of archaeological divers, working at depths of around 45 to 50 meters, captured detailed images of the wreck and surrounding seabed using advanced underwater photogrammetry, a method used to extract three-dimensional measurements from two-dimensional data.

Despite the challenging weather conditions, the research team, under the direction of Dr. Angeliki G. Simosi, Head of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Evia, and Lorenz E. Baumer, Professor of Classical Archeology at the University of Geneva, retrieved enough data to successfully create a 3D map of the site.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities

With funding from the Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation and Swiss Watchmaker Hublot, this latest round of work is the first stage in a new five-year research program (2021-2025) aimed at creating a better understanding of the distribution of artifacts on the seabed and a more complete analysis of the wreck.

An important part of that mission is the ongoing discovery and excavation of finds, including parts of the ship’s hull and cargo that remain exposed and vulnerable to possible looting and the adverse effects of the underwater environment.

Among the finds this year was part of a marble statue, found trapped under a large boulder. The team recorded the object by photogrammetry and will carry out a more thorough investigation next season. Also discovered were wooden and bronze structural elements of the hull, and ceramics that will provide further information on the composition of the cargo.

By integrating the results of past expeditions in one comprehensive database and 3D model of the site, the research team hopes to gain a more complete understanding of the ship’s sinking sometime in the second quarter of the 1st century BC.

© Marsyas

© Ishkabibble

Discovered in 1900 by sponge divers off Point Glyphadia on the tiny island of Antikythera, the wreck site was first described by diver Elias Stadiatis as a heap of rotting corpses and horses on the seabed. It was quickly established that they were in fact a pile of bronze and marble statues strewn among the boulders, the remains of an ancient cargo filled with luxury works of art and technology from the Aegean region.

A pioneering underwater excavation soon followed from November 1900 through 1901, co-organised by the Greek Ministry of Education and the Royal Hellenic Navy. During the course of their work, the divers, using canvas suits, bronze diving helmets and surface-supplied air through hoses, recovered 36 marble statues, and several bronze statues, including the famous “Philosopher” and the “Youth of Antikythera (Ephebe)” dating back to c. 340 BC. This extraordinary project led to the creation of the science of underwater archaeology.

But the best was yet to come. In 1902, while studying a number of concretions and lumps of heavily encrusted artifacts from the wreck at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, archaeologist Valerios Stais discovered the corroded remains of a piece of bronze with a gear wheel, bearing inscriptions in ancient Greek. Thought to be an early form of mechanised clock or an astrolabe, the object would come to be known as the Antikythera Mechanism, which many regard as the world’s first analog computer.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities

Subsequent investigations of the wreck site have yielded numerous finds, many now on display at the National Archaeological Museum. In 1976, the famous underwater explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau and his team recovered some 300 artifacts, including wooden elements from the ship’s hull, bronze and silver coins, gold jewellery, bronze statuettes, and, surprisingly, scattered human remains.

It is extremely rare to find human remains on ancient wrecks, especially in the Mediterranean. While skeletons have been carefully recovered from more recent wreck sites in northern European waters, famously from the 16th century English warship the Mary Rose in the Channel and the 17th century Vasa in Sweden, only a handful of human remains have been recovered from ancient wrecks in the Mediterranean. A recent analysis by researchers at Cambridge University of the bones recovered by Cousteau’s team found that they came from at least four individuals, including a young man, a woman and a teenager of unknown sex.

In 2012, a research team led by marine archaeologists Brendan Foley (then of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute) and Theotokis Theodoulou (Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities), conducted an extensive survey around the entire island of Antikythera using closed circuit rebreather technology and underwater propulsion vehicles, allowing for longer and deeper dives down to depths of 70 meters. During the course of their survey, a second ancient shipwreck was discovered, “wreck site B,” several hundred meters south of the Antikythera wreck.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities

In 2016, the same team discovered the well-preserved remains of a 2,000 year-old human skeleton, buried under half a meter of broken pottery and sand at a depth of 50 meters. Based on the robust nature of the skeleton’s femur (thigh bone), it is likely that the individual was a young man, perhaps a member of the crew. Nicknamed “Pamphilos,” after a name found scratched on a wine cup from the wreck, the remains were later sent for DNA testing – a feat never attempted before on an ancient shipwreck victim in the Mediterranean.

The current Greek-Swiss project will collate all the data from previous excavations to build a complete 3D map of the entire site for virtual access, enabling members of the public the world over to explore this remarkable shipwreck on the internet.

You can read more on the research team’s official website.