These days, quarantined in our homes and ever alert to the media’s latest reports on COVID-19, infectious disease is never far from our thoughts. Athenians, however, have been through all this before, more than 2,400 years ago. And even then, in the Classical late 5th c. BC, there was quarantine, panic, heroic self-sacrifice by the city’s health-care workers and fake news.

Something bad happened in ancient Athens in 430 BC, on that everyone agrees. Already the city was embroiled in a grueling “World War” against Sparta and its allies, whose hostilities had broken out the year before, and would rage on for nearly three decades. But Athens had a new problem, according to the historian Thucydides, at a time when many rural citizens had fled the Attic countryside and taken refuge inside the city-state’s walled “asty.”

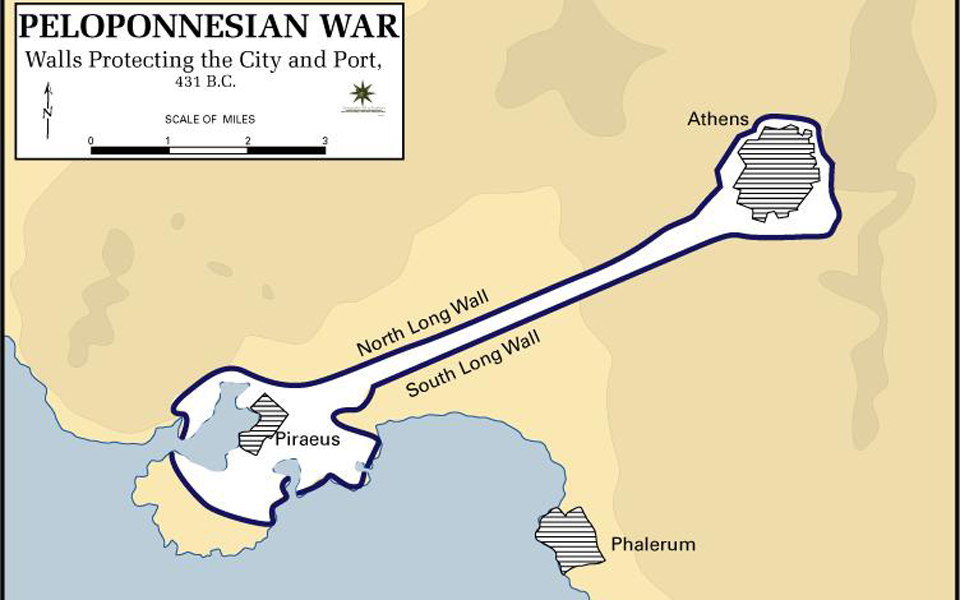

A plague, appearing first in Piraeus, swept mercilessly through the confined Athenian population. To add insult to injury, Athens’ great leader, Pericles, died in the autumn of 429 BC. Thucydides himself became ill, but survived to tell a tale of epidemic disease and grim misery that gripped Athens in the early years of the Peloponnesian War. Yet it seems there was much more to the story than what Thucydides reported. And it now is clear that the respected historian – on whom everyone since has relied for details of the plague – may have simplified, blame-shifted and exaggerated.

In the end, we have to ask, was there actually an Athens “plague”? And can we really conclude Pericles was among its victims?

An Eyewitness Account

Remarkably, Thucydides is the only ancient author who describes the late-5th c. BC plague in Athens (2.47-54, 2.57-58). The word “plague” is somewhat ambiguous, as it can be used to describe an epidemic generally, or the specific disease known as (bubonic) plague – the illness “caused by…Yersinia pestis, a zoonotic bacteria usually found in small mammals and their fleas,” according to the World Health Organization. In the case of Athens, Thucydides writes “the plague” (Anc. GR: h nosos), meaning “the illness/disease.”

“As soon as summer returned [430 BC], the Peloponnesian army…invaded Attica… They had not been there many days when the plague broke out at Athens for the first time. A similar disorder is said to have previously smitten many places, particularly Lemnos, but there is no record of such a pestilence occurring elsewhere, or of so great a destruction of human life” (2.47.2-3).

The historian is clearly referring to a single outbreak of disease, an epidemic, involving one illness. Since then, for more than two millennia, other historians and writers have followed suit, describing “plague in Athens,” “a city riddled with plague,” “the inhabitants’ fear of plague,” etc. But what sort of disease was it exactly?

Thucydides reports the symptoms and signs exhibited by the victims as if they all arose from one ailment. To emphasize this point, he states: “If any man were sick before, his disease turned to this” (2.49.1). His description of the illness’ indicators and progression is long and detailed (2.49), including extreme headache; red, inflamed eyes; throats and tongues growing bloody; breath noisome and unsavory; sneezing; hoarseness; chest pain and cough; stomach upset and vomiting; hiccups with strong convulsions; reddening skin with welts; internal heat (fever); insatiable thirst; dysentery; and finally death in 7-9 days.

Extreme cases, which nevertheless some patients survived, also involved gangrene, affecting the “privy parts,” fingers and toes; loss of the eyes (blindness); and an onset of “forgetfulness” (confusion, dementia). Altogether very unpleasant and speedily fatal, especially in an age long before antibiotics and other modern medicines.

© Public Domain

“The Spartans Did It!”

The initial outbreak of “the disease” in Athens lasted two years (430-428 BC), followed by a second, year-long wave beginning in winter 427/426 – “having indeed never entirely left the city, although there had been some abatement in its ravages…” (Thuc. 3.87.1).

All in all, the period of extreme illness appears to have lasted about 4-5 years. Thucydides reports the disease originated in “Ethiopia above Egypt,” spread into Libya, then suddenly fell upon Athens, first attacking the population of Piraeus.

The port city was alarmed, rumors spread and people claimed “the Peloponnesians had poisoned the reservoirs, there being as yet no wells there…” (Thuc. 2.48.1-2). Athenians also now remembered an old saying, “A Dorian [Spartan] war will come, and bring a pestilence with it.” And a past oracle, purported to have been given to the Spartans: When Apollo was asked “whether they should go to war, he answered that if they put their might into it, victory would be theirs, and that he would himself be with them” (Thuc. 2.54.4).

Today, such popular rumors might be considered conspiracy theories, urban myths or fake news!

The Human Toll

The effect of the disease on Athens’ military and civilian population was apparently devastating, based on the mortality figures Thucydides provides. In the summer of 430 BC, when Athens “made war upon the Chalcideans…and…Potidaea…,” the disease “devoured the army” and “Agnon…came back with his fleet, having, of four thousand men, in less than forty days, lost one thousand and fifty to the plague” (2.58.3).

Later, after reporting the disease’s resurgence (427/426 BC), the historian writes: “…the number that died of it of men of arms enrolled were no less than four thousand four hundred; and horsemen, three hundred; of the other multitude, innumerable” (3.87.3). Even more troubling, the plague was not the only current concern. Earthquakes were also suffered, “at the same time,” in Athens, Euboea and Boeotia (Thuc. 3.87.4).

The emotional, social and religious impact of the Athens Plague was pervasive. Thucydides (3.87.2) concludes “nothing afflicted the Athenians or impaired their strength more.” He paints a picture of timeless human nature, as panic, defiance, desperation and fatalism set in (2.53). Many of the city’s inhabitants resisted quarantine and succumbed to lawlessness, indiscriminate spending and a loss of faith in their gods. “Appalling too was the rapidity with which men caught the infection; dying like sheep if they attended on one another; and this was the principal cause of mortality…. For they went to see their friends without thought of themselves and were ashamed to leave them…” (2.51.4-5).

Pericles’ Death

Perhaps the most famous victim of the Athens Plague was Pericles. But was he? Thucydides (2.65.6) merely says: “He lived after the war began two years and six months,” i.e. until 429 BC. It is only from Plutarch, writing some 500 years later, that we learn “the plague laid hold of Pericles;” along with “not a few of his intimate friends,” his sons Xanthippus and Paralus, his sister, many other family members, and “those who were most serviceable to him in his administration of the city…” (Per. 36.1, 3, 4; 38.1).

Plutarch’s sources are rather murky, however, and it seems the biographer is either simply guessing as to Pericles’ cause of death or is guilty of spreading – again as we would call it today – fake news. Moreover, his description of Pericles’ final illness does not match Thucydides’ characterization of “the plague,” which rapidly dispatched its victims in 7-9 days or soon afterward (2.49.6). Instead, Plutarch writes (38.1), Pericles died “not with a violent attack, as in the case of others, nor acute, but one which, with a kind of sluggish distemper that prolonged itself through varying changes, used up his body slowly…”

© Shutterstock

A Mass Grave Unearthed

Archaeological evidence for an epidemic in ancient Athens was discovered at the edge of the Kerameikos in 1994-1995, when a roughly-dug pit was found containing more than 150 skeletons, accompanied by humble grave goods dated by the excavators to 430-426 BC. The deceased were laid out in a disorderly manner, in more than five successive layers, without any intervening soil between them (Efi Baziotopoulou-Valavani 2002).

Intriguingly, the pit seems to have lain open for some time (days, weeks?) – the burials in the lower levels were placed inside in a relatively more orderly manner than those above, which appear to have been heaped one upon the next with increasing haste. Children received more careful treatment, while eight infants were interred in ceramic pots. DNA testing of three adult teeth revealed at least three individuals in the mass grave had likely perished from typhoid fever (Manolis Papagrigorakis et al. 2006).

What Caused It? Modern Medical Theories

Many causes for the Athens Plague have been proposed by modern scholars and medical experts, including typhus, smallpox, typhoid fever, measles, bubonic plague, anthrax, scarlet fever, Rift Valley fever, Avian (bird) flu and even the Ebola virus! Overall fatality rates have been estimated at 25-35% of the Athenian population, based on Thucydides’ explicit mortality figures.

Certainly the epidemic was widespread and devastating, but most of the suggested illnesses can be eliminated, as they either do not fully suit the historical description or had not emerged until more recent times (e.g. Ebola in 1976). Smallpox is doubtful because Thucydides mentions no facial scarring. Ergotism (poisoning from contaminated food) could explain certain reported symptoms including the gangrene of the extremities, but epidemic typhus and typhoid fever seem the most compatible with the literary and archaeological/genetic evidence.

Typhus, already proposed more than 50 years ago by classicist A. W. Gomme, received further support from a University of Maryland analysis in 1999. However, in identifying the Plague of Athens with typhus, Dr. David Durack, like Thucydides before him, attributed all of the victims’ pathologies to a single disease. In 2013, archaeologist Karen Spence made a strong case for bird flu, but her study ultimately demonstrated that no single disease is a perfect fit for Thucydides’ historical description.

© Visual Hellas

© National Archaeological Museum of Athens

A More Complex Picture

Reality is full of complications and often messier than we might ideally prefer. Life in Athens during the early years of the Peloponnesian War was especially difficult. Inside the city walls, overcrowding, unsanitary conditions and poor hygiene were rampant – an environment conducive to both typhus and typhoid fever. Typhus is spread by fleas, which catch the disease from rats, but also by body lice and an infested person’s scratching or inhalation of louse feces. Untreated (with modern medicines), typhus is fatal in 10-40% of cases. Bird flu can occasionally be passed human-to-human through extreme, prolonged overcrowding, but usually through touching or eating contaminated fowl. Typhoid fever is spread through food and water contaminated with fecal bacteria. Untreated, it is fatal in 10-30% of cases.

War-time Athens’ cramped, hellish conditions were notorious, with Aristophanes jesting that residents even lived in casks, crevices and dovecots, blinded with smoke (Knights 795). Thucydides reports “dying men lay tumbling one upon another in the streets…” (2.52.2). And Sophocles seems to allude to the plague, when, in the opening scene of Oedipus Rex (ca. 430-423 BC), the Priest of Zeus describes Thebes much as what Athens must have been like at the time: “For the city…can no longer lift her head from beneath the angry waves of death. A blight has fallen on the…land… And the flaming god, the malign plague, has swooped upon us, and ravages the town…” [lines 22-30].

Typhoid is a waterborne pathogen, and, despite some scholars’ assertions, ancient Athens’ intramural water supply could well have been contaminated, especially as “men half-dead [gathered] about every well or fountain through desire of water” (Thuc. 2.52.2). The city’s wells were often interconnected, as shown during the Metro excavations (1992-1997), and it already had an aqueduct built by Peisistratus (6th c. BC) – sections of which were unearthed at the Syntagma and Evangelismos stations.

Food, too, may have been tainted, through spoilage or contact with ill cooks and caregivers. Consuming cereals contaminated with fungus would have had dire consequences; as would exposure to still-infectious human and animal corpses left lying about, and contact with scavengers that unwittingly poisoned themselves, including birds and particularly dogs (Thuc. 2.50).

An overloaded sewage system probably further added to the Athenians’ problems. Ultimately, the city of Athens was very likely plagued with multiple illnesses and numerous health issues during the period 430-425 BC, concludes archaeologist Torbjørn Iversen (2014), among which typhoid fever could have affected the broader population, while epidemic typhus struck mainly the poor and the refugees.

© Shutterstock

Appeals to the Gods

Archaeological evidence of pervasive illness in the 420s BC is seen not only in the Kerameikos mass grave and increased burial activity generally, but also in religious monuments and architecture. In seeking divine favor, the Athenians made appeals especially to Apollo and Artemis, the traditional bringers of plague.

In or near the Athenian Agora, John Camp notes (2001), statues were erected to Apollo and Herakles in their role as “Alexikakos” – Averter of Evil. On Delos, Apollo’s sanctuary was purified in 426 BC and the Delian games/festival reestablished (Thuc. 3.104). Furthermore, Athens built a new marble temple for Delian Apollo (426 BC), as well as a stoa at Brauron in Attica for Artemis (425 BC).

Healing sanctuaries were also established or enhanced around 420 BC, including the Asclepieion on the Acropolis’ south slope and the more remote Amphiareion in Oropos (north Attica).

Time For Reassessment & Further Investigation

Because of the importance of Thucydides and Athens in Western culture, classicist Robert Littman (2009) observes, the Plague of Athens holds a prominent position in Western history. However, “the plague” and its effects have long been overblown. Thucydides “apparently presents the total picture of serious diseases in Athens at the time” (Iversen 2014). Present-day philologists have offered a spectrum of interpretations, claiming the historian sought to contrast the tragedy of war and the pathos of the plague in Athens with Pericles’ high ideals expressed in his famous funeral oration (T. E. Morgan 1991), or even that Thucydides’ emotional description of the plague was intended as “trauma narrative,” meant to encourage public healing and preserve a collective memory of the ordeal (Jenna Colclough 2019).

It was indeed a terrible time in Athens, with uncomfortable, unhealthy living conditions, social upheaval and the post-Periclean rise of demagoguery, but did the plague really “contribute to the city’s overall loss of power,” or deal a blow “from which it never recovered”? The reality is that Athens suffered hardships from both war and widespread illness, which the war itself had caused.

Thucydides provides glimpses of this reality when he writes the walled-in Athenians “…were much oppressed… having not only their men killed by the disease within, but the enemy also laying waste their fields and villages without” (2.54). Also, the Spartans remained longer in their (430 BC) invasion of Attica “than they had done any time before and wasted even the whole territory…[over a period of] almost forty days” (2.57.2). Thucydides’ lurid details of “the disease” are morbidly impressive, but ultimately he was an historian, not a medical expert. He too easily blamed everything on a single disease.

Five centuries later, even Pericles’ death was blamed by Plutarch on “the plague.” Like today’s conspiratorial claims about the origin of the current COVID-19 virus, we must always be careful of fake news, ancient or modern – whether it is Spartan-poisoned wells (cf. Papagrigorakis 2013, “The Plague of Athens: An Ancient Act of Bioterrorism?”) or the death of a leader. Pericles may simply have died of old-age-related problems. He was 65 years old and the supposed manner of his death does not match Thucydides’ description of “the plague’s” symptoms.

One wonders if the Athens epidemic was actually as bad as Thucydides reports. Why is there such an historical and epigraphic silence concerning the illness? After all, Athenian theatrical contests never ceased. Were the seats in the theater of Dionysus’ empty, or did the venue hold the thousands it was capable of? Was there no public social distancing? An inscription of Lenaian festival entries (IG II2 2325) records several playwrights producing comedies between 429 BC and 425 BC, when Aristophanes’ plays first appeared, including Phrynichus, Myrtilus and Eupolis.

Additionally, the Hippolytus by Euripides was performed in 428 BC, followed by five comedies by Aristophanes: The Acharnians (425 BC), The Knights (424 BC), The Clouds (423 BC), The Wasps (422 BC) and Peace (421 BC). Yet no word of “the plague,” Perhaps some topics were just too painful to joke about.

Will We Ever Know?

The exact identity of the so-called Athenian plague is difficult to pin down. Like today’s COVID-19, the main illness affecting the city may have been a new virus. Disease profiles also change over time. The “plague” may have been caused by a pathogen that no longer exists. Its true nature may never be known. However, more extensive DNA study of the Kerameikos mass grave remains, with attention to gender and age differentiation, could provide more statistically significant, informative results.

Nowadays, we are more secure from disease, with improved environmental conditions, medicines and medical services, as well as more effective governmental controls and greater societal cooperation, but, as with the ancient outbreak, we will not soon forget this current calamity, when a dangerous plague has once again invaded Athens and our world.