Long ago, many people believed that human health was governed by the divine will of the gods.

During Archaic and Classical times (6th-4th c. BC), as philosophy, knowledge of the natural world and scientific inquiry flourished, especially in the fertile environments of Athens and the eastern Aegean, human beings began looking more and more to the healing powers of their fellow mortals, specialists in medicine, foremost among whom (at least from our modern perspective) was Hippocrates (5th/4th c. BC).

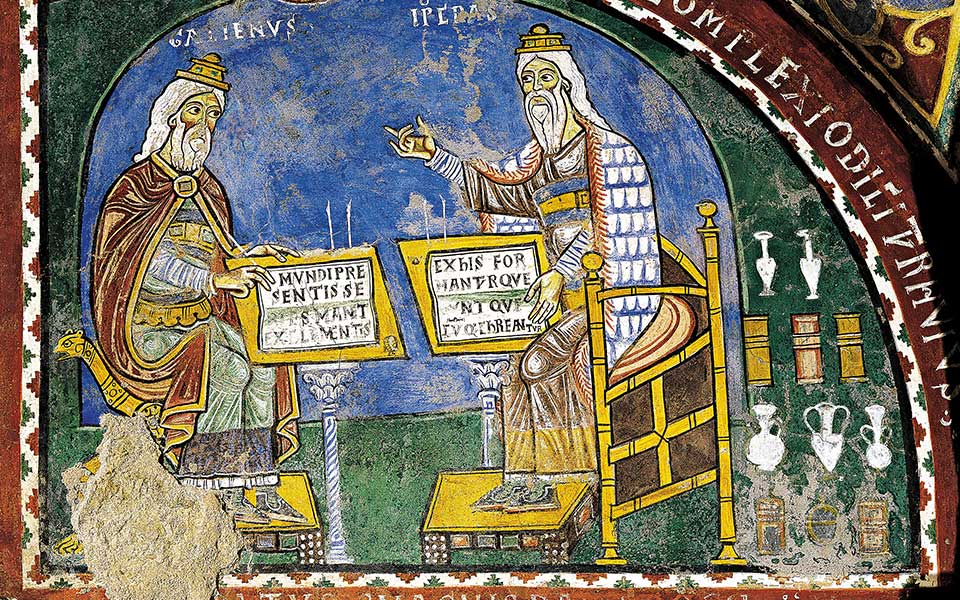

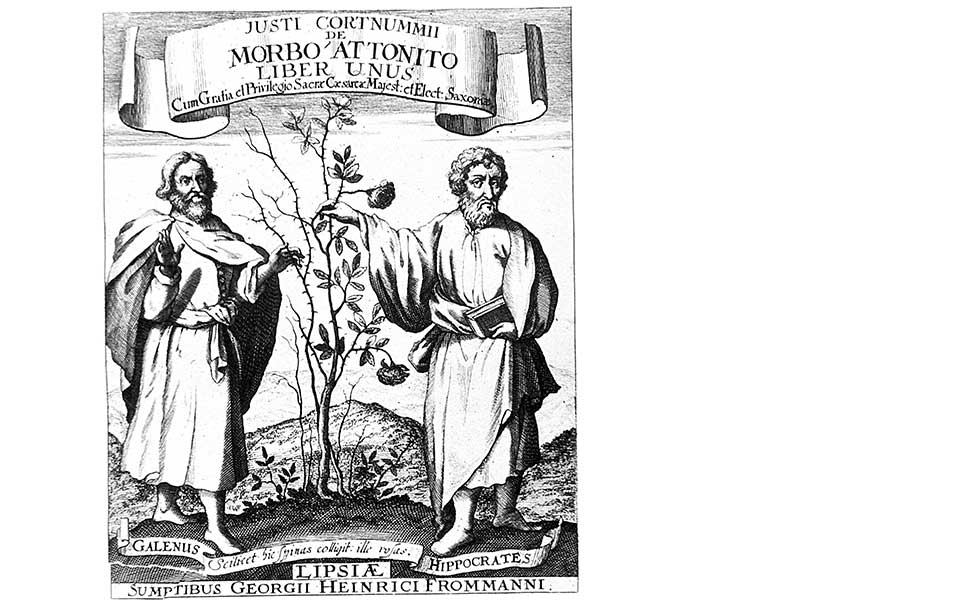

Later, as medical theory and practice continued to develop in the Roman era, Hippocrates’ legacy was carried on by Galen (2nd/3rd c. AD), whose own writings would also have a lasting impact on the development of modern medicine.

hippocrates

The founder of the science of medicine, this teacher and health practitioner is known as the “Father of Medicine.”

The name “Hippocrates” is well known among contemporary Western medical practitioners; new doctors are taught to learn and follow the Hippocratic Oath – a code of fundamental principles intended to encourage the proper administration of health care.

Hippocrates himself, however, remains a shadowy figure who apparently enjoyed a certain reputation in his day, but whose name at that time is only mentioned in passing by Plato and Aristotle. Detailed biographical information only appears some 1,400 years later, when Byzantine sources tell us Hippocrates was born ca. 460 BC, the son of an affluent doctor, Heracleides, and his wife Praxithea.

Hippocrates (died ca.370 BC) is most closely associated with Kos, his supposed birthplace. As a young man, he received his medical education at the island’s widely-known sanctuary of Asclepius. Hippocrates is said to have traveled widely in his medical practice, visiting mainland Greece, Egypt and Libya, before settling down later in life back home on Kos.

There, he founded his own school of medicine (late 5th c. BC) and taught a more science-based approach to healthcare, which separated the medical arts from votive religious worship and distinguished it not only as a spiritual or practical subject, but also as an intellectual one, worthy of philosophical consideration.

Plato took early notice of Hippocrates and his theories, writing in the Timaeus of the ethical implications and responsibilities involved in practicing medicine. This text greatly influenced later medical thinkers, in part by linking medicine with philosophy and health with politics, as well as by further underscoring the key interconnection between a healthy body and a healthy mind (Timaeus 88b).

The Hippocratic Oath is thought to have been composed by Hippocrates himself or by one of his students, sometime between the 5th and 3rd c. BC. Originally written in Ionic Greek, it called for physicians to swear by Asclepius and other gods that they would respect their teachers and, in turn, teach others; do no harm to their patients; maintain doctor-patient confidentiality; and defer to experts in surgical matters.

The Oath represents a timeless standard of medical ethics, even dealing with such still-relevant medico-social issues as the appropriateness of abortion and euthanasia.

The teachings of Hippocrates, now considered the “Father of Medicine,” are preserved in the Hippocratic Corpus, a collection of more than sixty treatises written by his followers. These formative texts, in examining the nature of health, illness and disease, describe good health as an equilibrium between internal “bodily fluids” and external, environmental and personal-behavioral factors.

Infirmity, then, arises from natural causes, not from divine punishment or supernatural sources.

a good diet

Hippocrates, like Galen after him, thought that health and disease were based on a state of equilibrium (or lack thereof) between four “humors” – bodily fluids consisting of blood, phlegm and yellow or black bile. Moreover (and more intelligible to our present-day medical sensibilities), this internal equilibrium depends on an external equilibrium between a person and their environment.

Hippocrates provides very modern-sounding advice for maintaining good health and avoiding disease, including: regular exercise; bathing with plenty of water and hot soap for good personal hygiene; eating a fresh, plant-based diet; reducing weight, as “those who are fat are more apt to die quickly than those who are thin”; drinking water and a properly chosen wine, but both in moderation; and keeping to a consistent diet and regular meal schedule.

Raisins, grapes, saffron, and pomegranates are healthful staples, but garlic and cheese can cause flatulence, nausea, and constipation. Too much water may encourage stomach gurgling; a poor or inappropriate wine can induce artery throbbing, spleen swelling, thirst and a heavy head; while skipping meals may lead to feebleness, heartburn, diarrhea, hot green urine and a host of other unsavory ailments!

Galen

Personal physician to Roman emperors, this scholar left behind a large number of significant medical texts.

The Greco-Roman world’s greatest physician, surgeon and philosopher was Galen (AD 129-ca. 216), born and educated in Pergamon (NW Asia Minor), a center of learning and home to antiquity’s second most important library. Like Hippocrates, he traveled widely, visiting Corinth, Crete, Cilicia, Cyprus and Alexandria.

After returning to Pergamon (AD 157) and serving as a physician to gladiators, he departed westward to Rome (AD 162). There he became personal physician to emperors Marcus Aurelius, Commodus and Septimius Severus. A specialist in human anatomy, Galen made great advances in the understanding of the nervous, the respiratory and especially the circulatory systems, including the distinct flows of blood into and out of the heart.

He followed Greek medical tradition in identifying a close interrelationship between mind and body, also introducing to Rome such Hippocratian practices as the drawing (phlebotomy) and letting of blood. His writings (in Greek), highly influential in the field of health, became a fundamental reference source in medieval medical education, later translated (1530s) into Latin.

A fascinating recent discovery highlights the extraordinary significance and cross-cultural spread of Galen’s medical texts. In 2009, high-tech analysis of a parchment manuscript revealed a 9th-century Syriac text beneath an 11th c. text of Christian hymns. The undertext is a partial copy of a 6th c. AD Greek-to-Syriac translation of Galen by Sergius of Reshaina, a Syriac physician and priest.

The Syriac Galen Palimpsest (SGP), as it’s now known, represents the oldest-known fragment (covering Books 6-11) of Galen’s treatise “On Simple Drugs.” In early Byzantine times, as Syriac-speaking Christians moved eastward from Anatolia into the Middle East, they needed translations of Greek medical texts to bolster their efforts in providing health care and establishing hospitals.

The Syriac language formed a linguistic bridge between Greek and Arabic, and thus facilitated ancient literature’s transmission into the medieval and modern worlds.

In the 11th century, the SGP manuscript was “recycled” by monks, probably at the Monastery of Saint Elias Shwayya on Lebanon’s Black Mountain, who overwrote it with hymns. It was later transferred to Saint Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai, where it was kept until being borrowed or stolen, and later offered for sale in Leipzig in 1922.

Now in Baltimore, Maryland, the manuscript has been digitally scanned, subjected to X-rays and other laboratory analyses, and is undergoing meticulous study by an international, multi-disciplinary team. The researchers believe this ancient “treasure” will further illuminate contributions made to the Western medical tradition not only by Galen, but also by the Syriac-speaking Christians of the Middle East.

in search of cures

Even more the medical scientist and researcher than Hippocrates, Galen was known for dissecting animals (mostly pigs and primates) and prescribing a wide variety of medicaments produced from vegetal or geological materials gathered from all over the Roman empire.

His travels in search of knowledge and pharmacological supplies took him both westward and eastward from his native Pergamon. For certain useful minerals, he sailed to Cyprus, where he “had a friend with a great deal of power on the island, who was also closely connected with the director of mines, and was the representative of Caesar” (“On Antidotes”). From there, Galen says, “I brought a lot of kadmeia, diphryges, spodion, pompholyx, copper ore” and other medicinal substances.

The “plakitis” (plank-shaped) type of kadmeia, he reports (“On Simple Drugs”), has cleansing and cauterizing power, to be used in the eyes and for moist, infection-prone sores or wounds – if the patient’s skin is soft, “like that of eunuchs, children or women; whereas harder, tighter bodies need more drastic cauterizing medicines.”