By Marianna Kakaounaki

Archaeologist Angelos Zarkadas began investigating the secretive repatriation of a looted ancient statue after reading about the case in a 2008 Kathimerini report.

His investigations into that particular head, which had been traced to the United States, however, also put him on the trail of another head that had been stolen from the same location. It has also ended up in a private collection – possibly trafficked by the same network – though this time much closer to the crime scene, in Greece.

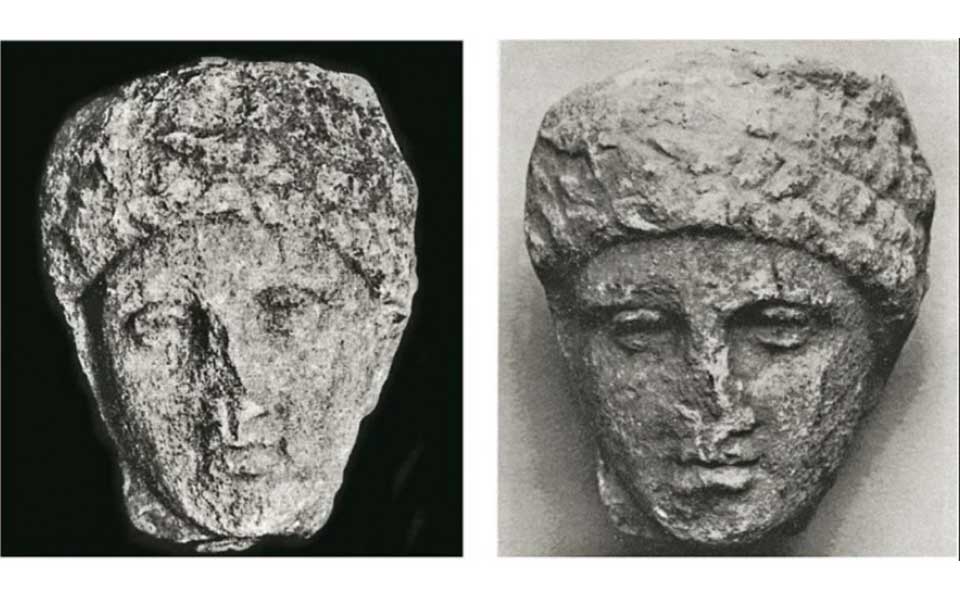

Zarkadas recently released the findings of his research in a two-tome publication by the Benaki Museum on the work of George Despinis (1936-2014), an archaeologist and researcher who had taken a photograph of the two heads in 1966 together with other finds from the Liopesi collection of artifacts excavated in modern-day Paiania (a part of Attica to the east of Athens). For years, the finds were kept in a room at a local school and were later moved to a basement in the same building in World War II, when the German used the room to store foodstuffs.

In 1967, a year after they were photographed by Despinis, the bulk of the collection – including the two heads mentioned above – was snatched by unknown looters. Where the pieces went remained a mystery for many years.

A Secret Rapatriation

In the late 1990s, a German professor of classical archaeology studying the two heads discovered that one of them had made its way to New York, where it was part of one of the biggest private collections of ancient artifacts in the world. The German academic was able to identify the head from the catalogue of an exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it had been shown in 1990.

Multi-millionaire Leon Levy and his wife Shelby White were renowned for their love of ancient Greek and Roman art and had a particular connection to Greece as a result of the close relationship they developed with the well-known antiquities dealers Robin Symes and Christos Michaelides. When they were informed by the German academic of the statue’s provenance, they agreed to return the head to Greece on the condition that no publicity was attached to the repatriation.

The artifact was returned to Greece a year later as per the agreement, which may also account for why it is not on display at the Archaeological Museum of Brauron (Vravrona), along with the rest of the Liopesi collection, and remains in a storage vault at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

While focused on the return of two other, better-known, artifacts from the Levy-White collection, the 2008 report by Kathimerini also mentioned the story of the head’s repatriation. It was this story that attracted the interest of Zarkadas and prompted him to go back to the original sources identifying the head: the annual Greek Archaeological Report of 1926 and the exhibition catalogue from New York’s Metropolitan Museum.

The Discovery of a Second Head

As he writes in the Benaki publication, the 1926 report held a surprise that did not have to do with the photographs of the already repatriated head, but with those on the next page. There, he saw a marble head that was very familiar to him. “The photograph of the item was a match for the marble head at the Paul and Alexandra Canellopoulos Museum, a fact that was confirmed by their dimensions and a close study of the sculpture’s details,” he writes.

It was clear from the evidence that after being stolen in 1967, the sculpture ended up in the private Canellopoulos collection through illicit channels. When and how this happened is still a mystery, though we know it would have been before 1972, when the collection was donated to the Greek state.

More lost treasures of the Liopesi Collection

Despinis himself had located yet another head stolen from the Liopesi collection. In an interview several years ago, he said that the sculpture had been traced to Switzerland with the help of Interpol and that once it was returned, archaeologists were stunned to discover that it still had the original Greek lot number imprinted on it.

The 1967 looters also got away with the top part of the funerary stele of Euthesion of Pallene that is currently on show at the Archaeological Museum of Basel in Switzerland.

The stele was also identified by Despinis in 1971 after he recognized the piece in a Swiss publication. Even though there is no question of the stele’s provenance, the monument remains split between two museums, though the Basel institution has a copy of the bottom part that was sent by Greece and is able to show what it looked like as a whole.

“What I want, as an archaeologist, is for the pieces to come back because they are clearly the product of theft,” Despinis had said at the time.

This article was first published on ekathimerini.com